Premortems and Postmortems Two crucial tools for writing code when the stakes are high, like...

Writing High Stakes Code (At A Startup)

Writing High Stakes Code (At A Startup)

.png?width=500&name=dice-1%20(1).png)

Thoughts on how to write code when the stakes are high or human safety is involved, but you don’t have the budget or timelines of NASA. Most of these are from safely building a fleet of over 100 robots at Cobalt, advising startups who programmatically move money/stocks, or my time at SpaceX. I’ll try to make this general for writing software in any high stakes situation, in any startup, and focus on where to get the most bang for your buck! – Erik Schluntz, Cofounder & CTO

Poka-Yoke

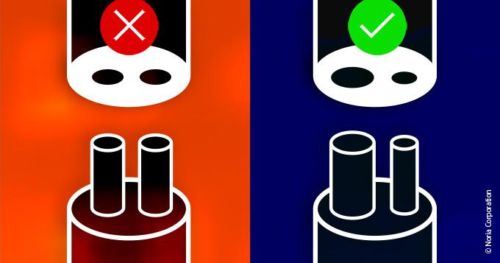

Poka-yoke is a Japanese term from manufacturing that means “mistake-proofing” by design. A common example is to make a plug non-symmetric so that it’s physically impossible to plug in backwards.

Fig 1. The plug on the left could be accidentally reversed, but the plug on the right wouldn’t fit

There was a real case of this crashing a Russian Proton M rocket because a square part was installed upside down. If the part was not symmetric, it would have been impossible to install upside down even if you tried.

Fig 6. Proton M rocket crashes on 7/2/2013 due to a sensor installed upside down

In software this is really important for dangerous tooling – think about what damage typoing a number could do in your provisioning scripts. You can make your scripts ask for confirmation if inputs are outside a normal boundary (if you just always ask for confirmation, people will just automatically hit yes).

Units, Naming, and Typing

A similar case is units – how much do you trust that everyone in the future will know whether this function expects meters, or feet, or inches?

do_critical_thing(float distance)

This exact mistake crashed the Mars Climate Orbiter in 1999 due to a mixup between metric units and imperial units. This could be avoided with a better variable name so anyone looking at the function is very clear what input is expected:

do_critical_thing(float distance_meters)

If you want to go even further enforcing type safety, you can import libraries that use physical units as custom types, that would prevent passing inches into a function that expects meters:

do_critical_thing(meters distance)

How many ways can one line of code fail?

One of the scariest things is needing to call a 3rd party or systems library in an important loop. This looks safe, right?

while True:

try:

do_untrusted_thing()

catch Exception:

print(“oh well”)

do_important_thing()

Nope! You can still get screwed over inside a try catch by either 1) a segfault in any library that’s calling C under the hood, or 2) the call hanging forever. Debugging the second case is the most infuriating, because it often doesn’t produce any logs – it just seems like your important loop vanished without a trace.

The safest way to avoid a function hanging is to launch it in a different thread running with a timeout. When our code interacts with the OS from python we never use subprocess.call(cmd) directly, we use a wrapper we’ve made called subprocess_with_timeout(cmd) that is guaranteed to return, even if the underlying subprocess call hangs.

Fig 7. Your code waiting for “ls -l” to return on a broken filesystem

Murphy’s Law / Simultaneous Failures

“Anything that can go wrong will go wrong.”

Given enough time and volume, you will eventually see problems that you thought were so unlikely you would never need to think about them. This is especially true of hardware, and as our fleet of robots has grown past 100 we’ve debugged some pretty weird things. Even with pure software, plenty can go wrong as you scale your number of users and servers. Your alerting provider will eventually have an outage at exactly the same time as you. You’ll have a user sharing their account with a friend modify their settings twice at exactly the same time. You’ll have hash collisions. Your server will run out of RAM right in the middle of an atomic transaction. You’ll get hacked.

If you think something is safe, ask yourself “If I simulated this for billions of hours / users, would the problem eventually happen”? If the answer is yes, it’s probably going to happen much sooner than you expect. Make sure you plan ahead for this.

Fig 3. Getting doubly or even triply unlucky will happen sooner than you think

Measure (and Alarm) what you make

One of my favorite questions for engineers is “How will you know your feature is working after you release it?”, and I’m a firm believer that merging and deploying new code is really the middle point of feature development, not the end. Increment has a great article, I Test in Prod, about paying attention to your code after it’s released.

This heavily ties into premortems: think before you release a feature how you’ll know if it’s successful, and how you’ll know if it’s failed or is unused. This could range from manual spot checks the day after a launch to building a new analytics dashboard for the feature.

What’s even more forgotten is the next question, “How will you know if this is still working 2 months from now?”, when those spot checks are over and you haven’t looked at that dashboard in weeks. Regression testing in CI can catch some of this, but there’s no substitute for the real world and Murphy’s Law. We like adding automated alarms to any new metric we create – Datadog and Pagerduty make this very easy. Creating a new metric without an alarm can leave you with a false sense of security that you have an eye on something, when really that dashboard will only be viewed during your next postmortem.

Fig 4. Software alarms are better than you at watching dashboards and raising the alert

Circuit Breakers

Sometimes it’s hard to spot an individual error, but in aggregate you can definitely tell that something is wrong and stop it. My favorite example of this is in any code processing stocks or money: it might be difficult to tell whether an individual trade was created by a bug, but if you see the same user making more than one trade per second, you should stop it.

You can implement circuit breakers with different thresholds at multiple hierarchies – one at the user level, one at the group level, and one at your overall company level.

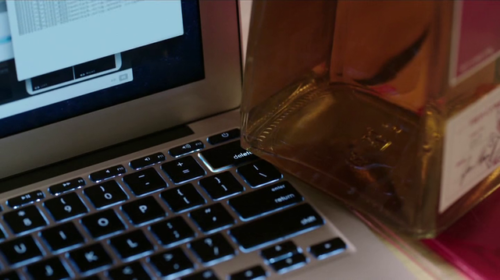

Fig 8. Pied Piper didn’t have circuit breakers on file deletion

Fault Tree Analysis (FTA)

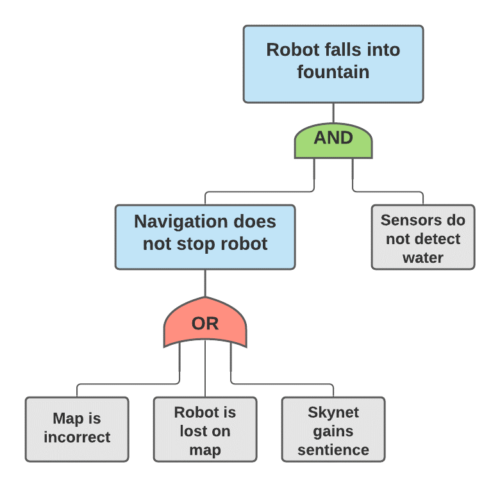

FTAs are a way to diagram and reason about failure cases through multiple lines of defense and spot where your weak points are. Think about what conditions need to ALL be true for something bad to happen, and that’s an AND gate, or think about several different things that could lead to the same condition and that’s an OR gate.

When you draw this out, you will get inspiration of where to add more safeguards (adding things to your AND gates), and remember to think at each level how human error could actually add an OR that skips right over your protections (i.e. “the alarm was left muted after a previous incident” or “No one remembered to set the feature flag for this customer”).

If you can guess probabilities for each of the root nodes happening, you can actually multiply through how likely failures will be to get all the way up to the top. I recommend only using these numbers to compare different branches, not to give you any overall sense of probability, because it’s so hard to estimate real probabilities of the root nodes.

Fig 9. An FTA of one possible robot failure

High Stakes Code at Cobalt Robotics

At Cobalt, we build autonomous indoor security guard robots that patrol through office buildings and warehouses looking for anything out of the ordinary for our customers. We write code that controls a 120lb robot navigating around people – basically an indoor self driving car, and our customers are relying on us to keep their most sensitive areas secure and protected. We’re hiring!

Fig 10. A Cobalt Robot patrolling an office space